PREMUS 2025: 12th International Scientific Conference on the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

PREMUS 2025: 12th International Scientific Conference on the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

Agreement between perceived physical workload and REBA scores in the automotive industry

Text

Introduction: Musculoskeletal disorders, including inflammatory and degenerative conditions affecting the back, neck, and limbs, are among the top causes of occupational injuries (Punnett & Wegman, 2004). In occupational settings, physical exposure assessment may rely on subjective judgments (e.g., checklists, questionnaires), observational methods (in situ or post-hoc), or direct measurements (van der Beek et al., 2017). However, these methods vary in accuracy according to their purpose, their measurement properties, and the evaluator (workers vs. experts). This pilot study aims to investigate whether perceived physical workload and direct measurements in an automotive final assembly setting agree.

Methods: Fifteen automotive assembly workers, mainly male (87%), with mean age of 36.5 years and seniority of 9.3±2.1 years participated. Postures were assessed with 17 IMU sensors at 60 Hz (Xsens Awinda Station, Xsens MVN Biomech™, Enschede, The Netherlands) attached via Velcro straps. REBA scores were computed in Movella motion cloud software (Movella, Enschede, The Netherlands). Workers self-rated their workload perception (neck, trunk, upper limbs, wrist, lower limbs) using a 3-level scale (low, medium, high). To compare self-perceptions with REBA scores, adjustments were made: Trunk, legs, upper-arm, and lower-arm scores were aligned to a 3-level scale. Upper and lower arm scores were averaged, as workers rated their perception for the whole upper limb. Kendall’s W coefficient assessed agreement levels and Wilcoxon test evaluated whether mean ranks for the perceived levels and REBA scores differ, considering p<0.05.

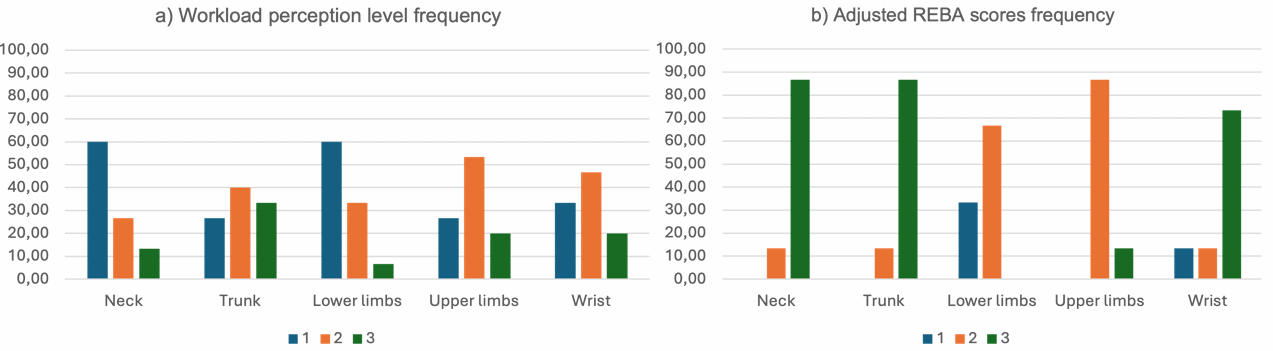

Results: Figure 1 [Fig. 1] shows both physical workload perceived levels and REBA scores frequencies Kendall’s W coefficient reveals no statistically significant agreement between perceived workload and REBA scores. REBA scores tend to be higher than workload perceived by the workers, suggesting participants may underestimate ergonomic risks. Wilcoxon sign-rank tests indicate statistically significant differences for the neck and trunk values (p < 0.05) but not for limbs or the wrist. These findings raise concerns about the use of self-perceived workload as a screening approach.

Figure 1: Physical workload levels’ frequency: a) perceived by the workers and b) assessed with REBA.

Conclusion: This pilot study provides insight into the validity of self-reported workload assessments compared with direct ergonomic measurements. The findings suggest discrepancies between subjective and objective assessments. Future research should explore whether ergonomic training may improve the validity of self-reported workload, enhancing risk identification and intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments: This study was conducted within the scope of the Wage: Healthy working environments for all ages: an evidence-driven framework, funded by the European Union under the Horizon Europe programme (Grant agreement ID 101137207), and supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through Grants: UIDB/00447/2020 attributed to CIPER – Centro Interdisciplinar de Estudo da Performance Humana (unit 447) (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00447/2020) and UIDP/04008/2020 attributed to CIAUD – Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design.